At the Annual South Asia Meetings this past week in Madison, Wisconsin, I organized a set of panels, with Gayatri Reddy and Martha Selby, on Number: participating were (in addition to we three) Sonal Acharya, Michele Friedner, Mather George, Ajay Skaria, and Harris Solomon.

The primary paper I gave was on UIDAI/Aadhaar. It was preceded by a somewhat more impressionistic set of comments on number designed to open the imagination as it were.

Both merit critique and so I am posting them here, though the first is tangentially relevant to UID, and both suffer from the limits of 15 minute presentations.

The conceit of the panel was that every paper be given a number as a title. My UID paper was entitled “1.”

Here it is, after the requisite picture of Madison.

1

Lawrence Cohen

A new and massive expansion of identity has been underway in India since the 1999 conflict with Pakistan known in the country as the Kargil War. Certitudes abound in the wake of this expansion: Geeta Patel yesterday spoke of a cottage industry of expertise. And yet as recently as this summer not only journalists and scholars but cabinet members appeared uncertain as to what the identity project was, whether it was legal, and who controlled it. I want today to offer what partial certitudes I can and to share some questions I face. Let me begin by summarizing my main assertion baldly. India is now a database. [Whether it makes sense to say that it has been a “database” in the past I would leave open for now.] For this nation-cum-database governance is being redefined as an “technocratic” operation that has been termed de-duplication. If we are to think about politics and economics in the age of the nation as database, we might attempt to understand both what may be entailed by the nation’s de-duplication, its reduction to a population of singularities, of ones, and, in contrast, what form, what thing, or what practice duplication of the one entails.

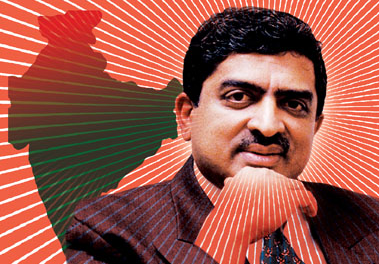

For duplication is a problem. The architect of the dominant version of the current expansion of identity, Nandan Nilekani the former CEO of the outsourcing giant Infosys, argues compellingly that India is plagued by leakage and inefficiency that dooms it to stagnation, illiteracy, and impoverishment and in effect keeps it, unlike China, out of history. This is the old Hegelian sickness from which China has apparently broken free. But India is awash in duplicates, precisely the symptomatology Hegel offered in the Aesthetics in his claim that for the Hindus spirit or divinity, being radically separated from nature, is indeterminate and can only take determinate form through a sensuous rejoining with nature: but a rejoining that must mark the primary ontological division between nature and spirit by exaggerating nature.

Thus Hegel’s example, of the deity image with multiple duplicate limbs or heads. If the deity is for Hegel an obvious monstrosity, for art historian Stella Kramrisch the accusation of an aesthetics of pathic duplication takes subtler form in her analysis of the logic of repetition that dooms the Idea, say of the hierophonic gopuram or shikara, to endless elaboration without the creative emergence of new forms. If some of the earlier Romantics and their varied, still extant successors could take India through Vedanta as in fact the Big One, the Truer One than the Abrahamic Trio of faiths always hesitant to embrace a monism sufficiently radical for Romantic apperception, Hegel and his varied followers, most notably Albert Schweitzer, would overturn the positivity of the Big Indian One and reveal it as a stunted singularity forever doomed in the punishing Hegelian terms to the duplication of the Idea and the profound negativity of Spirit in this frozen moment of the great dialectic.

De-duplication as an emergent project of technocratic governance assumes that India’s modern failures have been political and social. The accent is on the political: India’s social vastness, for the technocrats, could be leveraged as a tremendous resource but for the failures of its political system and the particular logic of the social it maintains. I will return to these key words, political and social, for they are floating signifiers whose content is being assembled under projects like de-duplication.

In his well-written and densely para-ethnographic manifesto Imagining India (the familiar title, of so many books, itself a duplicate and thus for Hegelians perversely unable to evade the punishing charge of the repetitive stutter of the Indian Idea), Nilekani argues that technocratic solutions to India’s problem with history are insufficient and that what we might call the political-social must be itself addressed. And yet the text carries a sense of the intractability of the Indian political-social, and thus of the need for a radical cure.

Drawing on my reading of Thomas Hansen’s well-known claim for a modern Indian anti-politics, one rooted in a rejection of the everyday play of interest as an always already corrupt nexus that can never be reformed and must be rejected for a sublime order of governance , I have in my earlier writings on family planning argued that a former Nehruvian technocratic regime came to rely on techniques and imaginaries of an as-if modernity, a surgical form of governance that worried that the masses, constituted not only as educable primitives but as a passionate mob ever outside of reason, could never be disciplined into the requisite abstemious Protestantism of the development project and must be operated open to be made to act as if they were modern and could withhold the passions. I termed this condition of as-if modernity that came to take sterilization as the technocratic condition to circumvent the intractability of the mass one of “operability.”

The logic of UIDAI, of the technocracy yet to come, I want to argue here, is not operability but de-duplication. Nilekani writes Imagining India as a second-order observer of the political social, in anti-political recognition of the intractability of the nexus, but his diagnosis of intractability leads him back to a technical solution rooted in an assemblage of techniques and forms: big data, biometrics, financial inclusion, and the conception of the state as a “platform” for minimal entitlement and labor rationalization through deterritorialized redistribution. I will explain what I mean by all this in a moment. But first let me schematize what to me seems the logic of intractability, or failure, that justifies UID.

The failure of the political might be called duplication-from-above. The failure of the social might be called duplication-from-below. That is, the wealth of the nation “leaks” away through corruption by a process of duplication by the ruling class and by the masses.

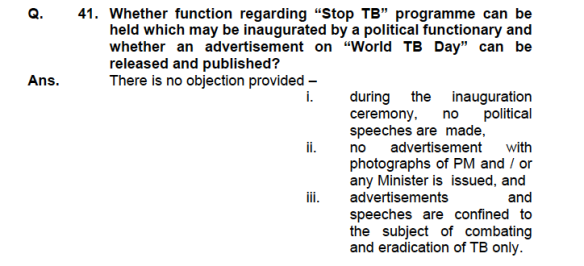

A politician or political nexus diverts wealth by mobilizing a phantom population of duplicates who on paper appear to be legitimate beneficiaries of, say, a cattle fodder scheme. A mass diverts wealth through countless tiny acts of duplicate identification, from mobilizing multiple ration cards to fraudulent pension claims and so forth. De-duplication would limit such bi-directional leakage by demanding a logic of identity through biometric ID cards and more critically big data collation and auditing creating a population that cannot be duplicated, or so the technical promise stands.

Through duplication-from-above and from-below, the wealth of the nation leaks from both its entrepreneurial acquisition by the new asocial business class (Nilekani presents himself as a self-made individual against the old business class of, say, the Ambanis and such for whom capital is deeply intertwined with irrational/corrupt social, that is familial, forms) and its redistribution to the new asocial and deserving poor (the new figure of the deserving poor is asocial to the extent the poor’s need is not “sops and subsidies” doled out to “local powers” but rather a generalizable distribution with a logic leading inexorably toward biological citizenship (to borrow Adriana Petryna’s apt term) through cash transfers).

That is, the deserving poor and the deserving entrepreneur are asocial to the extent their sociality can not be characterized by cronyism or nexus, the dominant signification here of the political social. What these twinned calls for what I am terming an asocial mass and an asocial form of capitalist reason produce is of course a new and presumptively rationalized and responsibilized form of the social, perhaps akin to what in different contexts Steven Collier and Jim Ferguson have conceptualized as a neoliberal social.

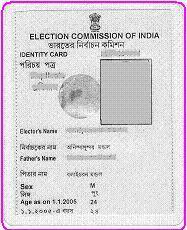

As many of you will know, de-duplication is to be achieved through a form of responsible belonging termed Universal Identification or UID, centered on an identity card branded as Aadhaar, literally “basis” but I which would translate in this case as “common platform.” The card’s promise is to create a de-duplicated and de-duplicable identity through several means of which I will discuss three. Each of these means moves past Hegel toward the One by a different numeric pathway. Since our discussions today are on number, let me reduce the complex technology of Aadhaar to a series of numerical operations addressing the means of getting to One.

To one through the random number

The first pathway is through the random number. “Biometric” data, principally two iris scans and ten fingerprint scans translated through “data capture” and a series of algorithms into a unique data set, are linked both to a physical ID card with a face photo and a randomly generated twelve digit number. Randomness is key for the architects of UIDAI: unlike the Social Security system in the U.S., in which the ID number is far from random and reveals data on birthplace, residence, and much else, leading to the possibility of gaming the system and producing duplicate (or in the US lexicon, stolen) identity.

In other words, a de-duplicated individual identity, call it the Little One, is to be generated by linking two numeric assemblages: a biometric data encoding and a random number, the latter in its utter randomness shorn as it were of the Idea and thus of the Hegelian sickness of duplication. And a nation of Little Ones, achieved through their agressive de-duplication, constitutes the ever deferred Big One.

To one through the zero

The second pathway is through the zero. No one is to have access to the database. What I mean by database is the series of servers and data architectures that link a random number to a given biometric profile. The engineers who have designed Universal ID, a number of whom I have interviewed in this very early stage of my own research, put great stock in this zero. It is both their response to the dominant criticism of UID, its potential invasion of privacy by the security state, and to their primary concern, that the Aadhaar card far from de-duplicating India will only be the most cunningly designed engine yet for the creation of duplicates. The system creates a random Little One identity that cannot be accessed by anyone. Not its architects, not its outsourced ID card registrars, not bureaucrats, not politicians, not you, not I. Only the data architecture itself, if I understand it correctly (and my research is now, and at this point unlike the promised card quite fallible), can “know” the referent of the random number, can trace it to the individual, the Little One who its creates and guarantees. But no human knowers can penetrate this knowledge, or pervert it to political-social ends.

UID thus produces an extraordinary form of power that in its promise of incorruptibility is subject to and transparent to no one, a power that in its apparent ontological grounding in the zero I will for now at least term bodhisattva power. It is the opposite conception of de-duplication from that advocated by proponents of the Right to Information and their conception of a social audit, in which Security can only be grounded in the Multitude, in a form of number not zero, not one, not random.

To one through the two

Each of these pathways presumes a limit in the current political social as a control or command polity, a kind of failed Big One. The state and the political class are responsible only to themselves: politicians will not have the incentive to implement a project of this scale and bureaucrats will not have the incentive to generate the universal biometric registration of citizens. The third pathway is through the two. By two here I refer to the emergent structure of government that addresses the presumptive failure of ordinary bureaucracy and ordinary politics by creating an exceptional outside to the state, but one that becomes in effect a parallel or second order of government, the one that promises to succeed where the ordinary government is always assumed to fail. This doubled assumption, of success and of failure, is what I refer to as the logic of the two.

The establishment of UID as an exceptional branch of government, along the lines of the successful Delhi Metro (but also the failed Commonwealth Games), follows a logic of creating an outside to the normal state, perhaps or perhaps not in itself a duplicate, a thorny question to which I will return in a moment in closing. The UID Authority under Nilekani infamously carries no statutory authority and though it is housed in the Planning Commission under the Finance Ministry is said to carry informal “Cabinet level” independence as an executive unit.

And exceptions, or outsides, proliferate all the way down, not just at the Cabinet level. UID outsources its registration in diverse ways, primary to private companies who again produce a new outside to the normal state, but also to NGOs and perhaps most interestingly to state governments, with whom quasi-contractual obligations are set up using a range of documentary forms like the MOU. UID identifies this outside to the normal state as an “ecology,” utilizing para-ethnography to figure out what particular combination of corporate, social humanitarian, and state agencies in a given region or among a given target population should be used to create such an outside.

Last thoughts

My time is numbered and I can here only hint at what is already for me a complex set of questions in the face of de-duplication and the demand it makes for us to specify what actual politics and what actual ethics may emerge in its wake as a mode of as-if governance. It should be clear that I am at least for the present not interested in playing the dominant game shared right now by some news media, much of the left academy, and the BJP: that is, in multiplying instances of where UID and the varied ecologies it is setting up have failed. I will like others be over the next few years charting and thinking amid such varied outcomes and effects. But I think we need to pause and look carefully at what de-duplication is before we take the high road of easy (and often undoubtedly justified) denunciation.

Let me close as I opened, with identity as a project that does not produce clarity, and say more about what I meant. UID began as a very different project. The Kargil Commission proposed a biometric ID card for Kashmiris: the burden of data would be highly territorialized, focused on the Reason of Security and the assessment of whether a subject was in the right place. The political impossibility of that Kashmiri only card led to its “universalization” as a National Population Register under the Home Ministry. But Manmohan Singh soon moved the project of the nation cum database out of Home and into Finance and brought in Nilekani to reframe the database in terms of financial inclusion and labor flexibilization through a common biometric platform, a different path to the Big One.

The new program required a fraction of the data fields of the older one and initially stressed deterritorialized identity, enabling or so it was promised entitlements without maintaining a life-time relationship to one’s father’s village or mohalla. By January of this year, the then Home Minister Chidambaram asked the Prime Minister to decide just how many nations-cum-databases there were. The relation of the security focused national Population Register to the liberalization focused UID was clear to no one, or so it seemed.

Negotiations continue. What is extraordinary is that the very regime of de-duplication that was through big data and biometrics to force India back into history and its rightful place as the Big One was itself, well, duplicated. The national database, Chidambaram claimed this past January, is now itself troublingly duplicated, and this he forcefully argued was a state of affairs that could not be allowed to last. Nilekani, characteristically, remained silent, perhaps following the pathway of zero. We are left to wonder whether de-duplication requires its own duplication, and what, as the random numbers proliferate, that may mean.