A brief comment today riffing off of a set of lectures and seminars given by sociologist and anthropologist Veena Das at Berkeley a few weeks ago. Das and many colleagues have long worked in several slum areas in Greater Noida, an extensive area of urban development including large tracts of slum housing far to the southeast of the older urban core of Delhi.

This work has long troubled the sufficiency of figures of “the poor” and “the slum” and their presumptive “everyday” reality, through long-term weekly and monthly inquiry by a team trained by Das into well-being and illness, income and expenditure, relations to politicians, brokers, bureaucrats, healers, and much more. Through “amplificatory techniques,” these weekly and monthly engagements have produced a dense and complex record challenging the adequacy of much urban slum ethnography that all too moves quickly from (1) single case studies, in or across widely separated moments in time, to (2) generalized accounts of “the poor,” of conditions and of processes in the slum. What Das has argued is needed is a very different form of research.

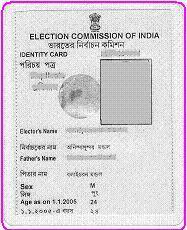

One of my concerns in this emerging project has been “duplication-from-below.” UID/Aadhaar is premised on ending “leakage,” regularizing and rationalizing state (and increasingly privatized) development and basic entitlements enabling life with an (allegedly) incorruptible ID card that uses biometrics and big data to eradicate all “duplicates” — that is, to end cheating with duplicate IDs. Duplication-from-above is the diversion of entitlements by a powerful “nexus” (usually named as politicians, parties, land mafia) that creates a phantom population in order to siphon benefits on a massive scale. Its opposite in formal terms is a duplication-from-below by which less empowered people get by with multiple (“duplicate”) ration cards, false (“duplicate”) addresses, and so forth.

De-duplication, the new order of information promised under Aadhaar/UID, is of course premised on ending both. If the new order threatens livability by depriving more marginal persons of the tactical resources of duplication, the benefit will be the legitimate flow of currently throttled entitlements and greater wealth and health for all. Or so the promise of the card is framed.

One could look at life in the areas studied by Das, her colleagues, and their research team as intensely “duplicated-from-below.” But the rigor of the amplificatory method they employ has allowed them to place what I term duplication in real time, as it were.

Let me give an example of duplication, from a paper by Das, and how it might conventionally be read. Then let me apply the discussion she offered during her Berkeley visit to rethink the problem of the duplicate in time.

Hospitalization through duplication

The example comes from an essay entitled “TB and Urban Poverty: An Essay Critical and Clinical” that can be found on the web. It centers on Meena, “a resident of a cluster of jhuggis (shanties) in the industrial area of Noida.” The cluster or slums is specific in several ways: (1) Waves of settlement: “The residents of the jhuggi settlement in our sample had arrived in waves – the earliest settlement can be traced to forty five years ago. Subsequent movements have followed networks of kinship and village affiliations.” (2) Complexity of the multiple norms structuring informal rights in land: “The settlement is an unrecognized colony which means that the residents do not have a legal right to the land but complicated customary norms have evolved here as in many other slums of this kind, so that people have ‘bought’ land and built jhuggis on this land.” I will return to this complexity as a particular condition of duplication: given the lack of a formal norm of occupation of land, provisional and contested norms proliferate. (3) Eviction stay, election cycles, and perennial hopes of formalization of rights in land: “The residents have also registered themselves as a scheduled caste association … [which] has enabled them to obtain a stay order … [forbidding] the government to take over their land unless alternate housing is provided to them. The government policy on this issue has vacillated over time but with each election, as residents are courted by candidates, they become hopeful of getting rights to pakka (i.e. built with bricks and cement) housing in a ‘recognized’ colony.”

Some initial context is offered on Meena: (1) Household: she lived “with her husband, two young sons and the husband’s father.” (2) Family tensions: “Her two sisters were married to the two brothers of her husband but relations between them were fraught with conflict.” (3) Employment and income: “Meena’s husband and his father were both employed by a contractor in the U.P Water supply department as cleaners. Thus they had a stable but meager income throughout the period of our study which meant that small amounts of cash were available to the family, though this cash was never adequate for the many demands ranging from food, providing school supplies for the children, as well as money spent on alcohol and tobacco by Meena’s husband.” (4) Clinical expenditure: “there were regular expenditures incurred on medications, especially as the younger son suffered from a respiratory ailment.”

The fieldworkers’ account of Meena’s TB shifts. Initially in 2000, “Meena had reported that her first episode of TB occurred three to four years ago. At that time she said that she took medications for a long time – perhaps seven months, perhaps one year.” But later “she said to one of the fieldworkers that she had TB for the last eight years which had ‘never been cured.’ She described a complicated story in which first, she talked about a breast abscess after her child’s birth, a minor surgery as well as fever, cough and weakness.” The earlier period of TB occurred when she was still in the village. Meena took medication until she became asymptomatic or even remaining weak given the lack of money. After she went to a local BAMS [Ayurvedic Medicine] practitioner who gave her antibiotics, analgesics, and other medicines. Her need to get well was intensified by the fear that her husband was seeing another woman.

Their relation worsened, as did Meena’s health: her husband did not have enough money to get her admitted to a local private hospital but her cousin got her admitted to a government hospital at some distance “under another name in that hospital on the pretext that she was his dependent relative.” She stayed there 6 months. The research team could not find her for some time as her name had been changed: one of her sons also worried that his mother had died. When she returned home, “the hospital discharged her with instructions to complete the course of medications. She was required to go the hospital OPD to receive medication but her husband managed to get her name transferred to another DOTS center nearer their home.”

Meena’s health improved for two years. Her symptoms then worsened and the researchers took her to a clinic they knew at some distance again from the slum: the doctor there confided that he did not see much therapeutic benefit given likely MDR-TB [multi-drug resistant TB]. Again the distance was hard for Meena’s husband, he “did not want her to be admitted to a hospital so far away from home so they went to another DOTS center by providing a false address. Here again she was dispensed the anti TB regimen under the DOTS protocol but reported serious side effects such as continuous nausea. Her condition continued to worsen, so she stopped taking medications. She died in a private nursing home in December 2003 where she was rushed in the last two days of her life. The family at the end of her life was in debt to the order of several thousand rupees.”

Das’ essay uses Meena’s story to challenge the dominant account of much of the public health and anthropological literature: that stigmakeeps people from returning to clinics and adhering to an adequate course of anti-TB treatment. Rather: “what seems to emerge from the story, instead, is consistent institutional neglect and incoherence. This neglect exists in conjunction with the care and neglect built into Meena’s domestic relations. In the course of three and a half years, Meena took three rounds of TB medication, all under the protocols of TB management in DOTS centers. There was no consistent record of her illness with any of the practitioners. When she was admitted to hospital, she took an assumed name and did not show her previous medical records but even when she used her own name there was no attempt on the part of the DOTS center to ascertain her medical history. In each episode of the disease she completed the course of medications, and was declared to be sputum negative and thus ‘cured.'”

Das suggests that the particular practice used by Meena’s husband to get her into a DOTS program or treatment center closer to home, what I am terming in relation to the language of UID as “duplication,” is also not enough to explain why clinics never treated her in relation to her previous medical history.

Still, a pattern emerges: care from the wage-earning husband is inconstant and Meena depends both on him but on others (her relations, social welfare agencies [here the research team] who use their own connections to get her seen far from home. At some point when her husband becomes involved in her care he moves her back closer to home. These moves may involve a “duplicate” name or address change. Whether or not the care network resorts to duplication, the clinic seldom attends to Meena’s past history of TB in prescribing.

Duplication as access to care?

Duplication-from-below emerges here as a resource–for the relative who moves Meena to a government hospital and for her husband who on two occasions moves her care closer to home.

But Das and colleagues show that whether or not the care network “duplicates” Meena’s identity to get her admitted, her de-duplicated medical file is not utilized.

The context, in which the Government of India’s failure to organize effective DOTS treatment for drug resistant TB has led to calls for UID to be used to deterritorialize TB care and create incentives and demands for de-duplicated patient identity, is critical: in theory, allowing for the mobility of the patient file through UID/Aadhaar could lead to Meena’s information following her clinical trajectory. But the very structures of diagnosis and assessment have produced a body of knowledge which asserts that practitioners, most with substandard or nonexistent training, do not need such long-term mobile knowledge to treat people like Meena.

UID promises de-duplication, deterritorialization, and thus better care. The shifting availability of care from husband/husband’s family and her own family/outsider welfare have demanded that various persons in Meena’s world duplicate her in order to deterritorialize her care. And at some level, heretofore Meena’s duplication or de-duplication does not seem to change the quality of care as the clinic, despite the prevalence of MDR-TB, continues to treat each episode as a singularity.

Will a new demand for Aadhaar that makes duplication-from-below more challenging change the situation in terms of clinical norms of treatment? The sense one gets from this paper is pessimistic.

The accusation of address

Finally, Das at her Berkeley talks made a point that echoed one with which I began discussing this paper. The complex conditions under which slum residents may make some kind of normative claims on state or corporate or NGO programs lead to the multiplication of addresses. Programs often mandate audits of the informal slum and may find previous systems of house-numbering to be inadequate or untrustworthy. Numbering systems proliferate. Das described a given slum area that had some 4 or 5 parallel numbering systems each created by a specific agency of slum governance or welfare.

At stake in the duplication, that is, may be an intensification of the accusation of untrustworthiness. Slum-dwellers are accused of cheating, of duplication, and are assigned new numbers, a presumptive de-duplication. But each effort to de-duplicate only intensifies the condition of duplication and the accusation.